hist_img:

red scare propaganda

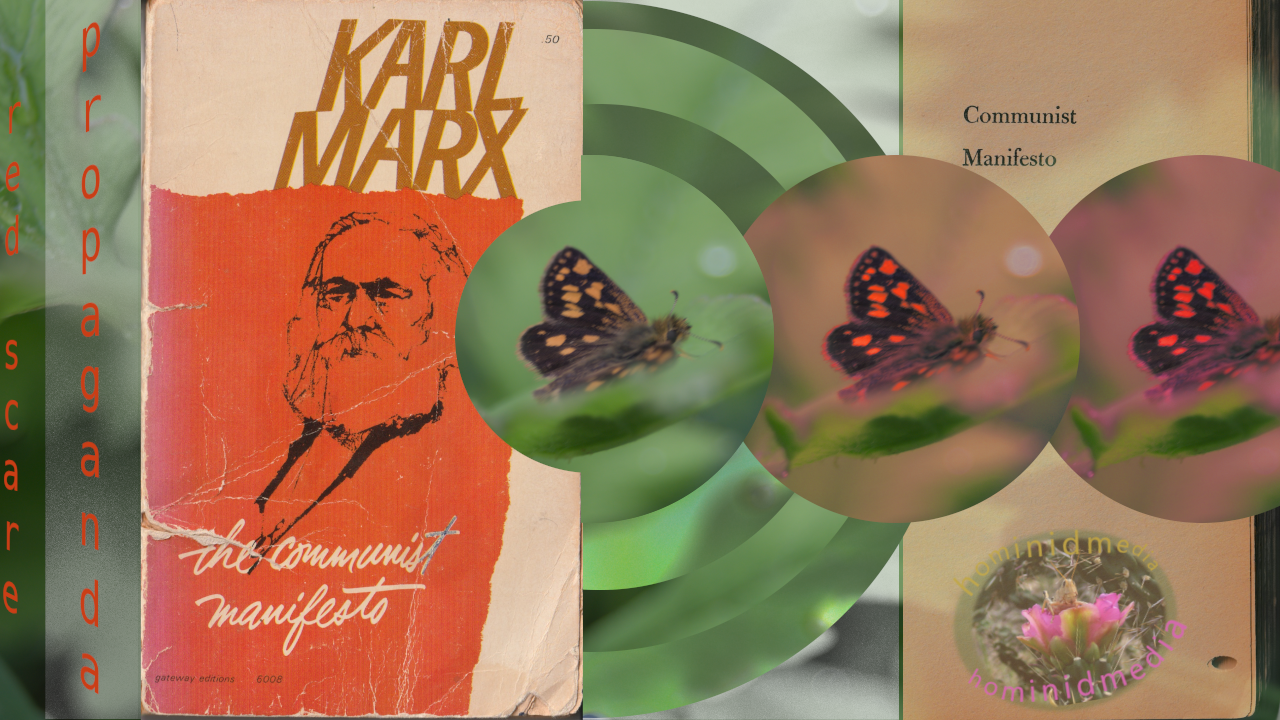

My mother's copy of The Communist Manifesto has a worm hole that crawled through the first forty leaves on a hydrostatic skeleton. The spine is broken and the and the pages are yellowed, rough and brittle. It smells like musk, dust and the inside of old wooden desks. She remembers it as a symbol of a rebellious high school phase. It didn't make her a communist.

A reprinting of the Samuel Moore translation featured on <marxists.org>, the Regenery Co. Gateway Edition published in Chicago about one hundred and twenty years after Marx wrote it. My mom's copy was of the eighth edition, printed in 1965. The cover features a faint etching of Marx--with furrowed-taught woolly-bear caterpillar eyebrows--in front of a blazing red background: "KARL MARX"--"the communist manifesto." Working men of all countries, Unite!

The worm ate through an introduction to the 1954 first edition, by Georgetown professor Dr. Stefan T. Possony. He is also credited as "of the Hoover Institution," on the back cover. Regenery, Gateway publishing, the Hoover Institution and Possony reveal intentions contrary to the portrait of a Prussian philosopher with a supraorbital pouf.

This paperback appears to be a radical text. An introduction for potential New Leftists awakened to consciousness by SNCC, SDS, BPP or Youth International. This could be a book that reorients a reader's struggle within a longer left history obscured by war propaganda, 100% Americanism and red scare anti-communism. Based on its cover art and funky musk, this book might have been purchased at an independent bookseller next to incense, tapestries and (perhaps) a velvet blacklight poster of a Hookah-Smoking Caterpillar.

Radicalism is the adolescent urge projected by my teenage mom through this book. She shocked grandpa's boss' son, Billy Stiefel--with the Hegelian gaze circa 1967. This was years before the pages desiccated yellow and idiomatic bibliophile bugs gnawed beneath Dr. Possony's words. The introduction mostly satiated the bookworms. They nibbled on Marx, through the "Bourgeoisie and Proletarians" but had enough by "Proletarians and Communists." The critters never made it to to the substance of the Manifesto.

There is undeniable giddiness in carrying around transgressive literature. This exists without reading it. The radical power of this book--overthrowing capitalism--is not possible through adolescent posturing. To consciously transform: from a-very-tiny caterpillar to a-big-fat caterpillar (or crimson-winged butterfly), one needs to consume valid theory and not fill up on junk.

During the Cold War, a curious teenager had to overcome discouraging cultural messaging and social stigma to actually acquire a copy of Marx. Even then, their copy might be veiled right-wing propaganda. That is case with my mom's copy of the Manifesto. Dr. Possony's introduction muddies a solitary student's early experience with class consciousness. In a classroom it creates insufferable students with baseless opinions. The Communists' greatest strengths--scientific method and clear communication--are confused by the introduction's anecdotal logic and unclear purpose. This is by design.

The publisher, Regnery, released right-wing texts like The Conservative Mind by Russell Kirk and the "Human Events" newspaper (founded in 1944, online from 2013). Dr. Possony was an Austrian who fought against the Nazis. He became an academic hawk in America after the war. He was a master of psychological operations and chief advocate for the Strategic Defense Initiative (aka Star Wars) during the Reagan administration. Both Regnery and Possony were virulent and outspoken anti-communists. Judging this book by it's cover, the right-wing politics is only visible through Possony's affiliation with the Hoover Institution.

In the first paragraph of the intro, "The Confiscation of Human Liberty," Professor Possony explains many copies of the Manifesto have been printed but few have been read. This hints at the goal of this Gateway Edition: preconception and prejudice of a first-time reader. A second goal might be exhausting the reader--until they feel like a bloated snake struggling to digest a piece of putrescent meat--before the text even begins.

My teenage mom read the Manifesto with a pencil so I can observe Professor Possony's psychological operation in action. The introduction is thirty-four (xxxiv!) pages long and heavily marked. The Manifesto's seventy-one pages are barely touched. Engels' intro is wholly untouched. The part that appears to have been noodled by my mom was Possony's pre-buttal.

The intro relies upon straw-men. For example, Dr. Possony (channeling Werner Sombart) critiques the Manifesto's originality, "Marx is as little the originator of socialism and communism as the chairman of General Motors Corporation is the inventor of the automobile." [xxi].

Neither Marx nor Engels claim to have invented socialism or communism. In the attached text, Marx' Communist ideology is "in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer..." Originality is the conservative critique but their underlying bourgeoisie fear is the Communists' systematic, scientific method for studying and influencing political economy and social movements. The purpose of this method is "...formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, and conquest of political power by the proletariat." [40] This class based, historical analysis (not communism itself) is the contribution claimed by Marx and Engels.

This method is different than "communism"--which is a trans-historic socio-economic phenomenon including mode of production. The development of this phenomenon is detailed by Engels in "The Origin of the Family" (1884). Rather than claiming to have invented Socialism, Engels is a Scientific socialist in a dialectical relationship with the Utopians socialists that preceded him. [see: "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific" (1880)]. This is basic Communist theory, clearly communicated and widely distributed. With it, an expert like Professor Possony is familiar.

He does not address the Communist oeuvre in his critique of an opus. Instead Dr. Possony centers an early contemporary critic of Marx, de Tocqueville. The introduction lists Marx' inspirations as if communists prone to plagiarism instead of theoretical pugilists with penchant for citations (xv-xx). Possony then notes that Marx "did not read" (his italics) Democracy in America and therefore the Manifesto "was based on less than complete factual information" [xxi].

A petty critic might wonder why Dr. Possony doesn't include other contemporary theory and method, beyond de Tocqueville, in his critique. For instance, the Second Epilogue of War and Peace. In it Tolstoy debunks the Great Man theory of history (after writing all those pages about Napoleon)--which seems to be a goal in line with the communist international and contrary to Possony's elevation of de Toqueville. Or the Turnerian Frontier school from Madison (WI). The concept of generations of homesteading altering social character through savage natural (and transcendental) variables adding depth to nationalism is something Possony ignores with an economic analysis of individualism.

Tolstoy, de Tocqueville and Turner are fine historians with different methodology than the communists. They are theoretical red herrings used to distract from the text by petty critics. The most convincing thing about Capital--the dismissal of Mercantilism--is achieved by Marx as he hoists Ricardo, Smith and Malthus by their own formulae, rules and tendencies. The thinly veiled post-classical economics of Possony haven't corrected for structural unemployment, poverty, monopolization and poverty--the liberal reality.

Dr. Possony portrays Marx the monolith representing communism and the dialectic based only on the Manifesto. This is a critical misunderstanding of the scientific method and economic development. That is to say, Marx' prescriptions for 1848 Europe might not apply to the American milieu of the civil rights movement where my mom picked it up. The dialectic is interpreted by different scientists--through experimentation. The same method that suggested internationalism to Marx, Lenin and Trotsky yields nationalism elsewhere. Versions of socialism with national characteristics are part of the communist oeuvre proposed by Stalin, Deng, Tito, and Kim. Gaddafi and the Bolivarians promote a third world regionalism that outlived the relevance of the non-aligned movement. Possony doesn't need to critique every communist in history but the focus on one treatise stuck-in-time ignores the theorists that followed. A longitudinal perspective and context is what many introductions provide not a direct rebuttal of the text.

Dr. Possony chose to focus on de Tocqueville, a French republican who wrote favorably about America's democratic institutions emphasizing equality and individualism in Democracy in America. He did this while a diplomat for the July Monarchy (1830-48). This regime was ended by a wave of European revolution predicted in the Manifesto called in France the February Revolution and Second Republic (1848-51). The Republic also employed de Tocqueville. He retired in 1852 when Napoleon III's Presidential regime became a monarchy. De Tocqueville was a State employee without prejudice. He served a feudal king and bourgeoisie president. Contrast this to Marx, who provided a model for withering the State in the industrial era through democracy, socialism and communism. Marx' proletarian revolution used the same method as the capitalist revolution that destroyed feudalism--the revolution that de Toqueville was on the wrong side of, twice. The men had two different theoretical goals within a broader political economy.

Early in my history studies, my father gave me a copy of Democracy in America for Christmas. It is a nicely bound Everyman's Library edition (New York: Knopf [1994]) with a hard cover and ribbon bookmark. This is a regal and bourgeoisie book fit for de Tocqueville. This is especially evident when compared to the tattered paperback hand-me-down copy of the Manifesto. In middle class America, this is how the two were framed: one for polite society and one for the lumpen worms.

The Communist method of dialectics requires a test of conflicting theories in the service of scientific truth. Take the Utopians for instance. Marx picked apart classical economics in Capital. Engels digested Anthropologist Lewis Morgan to produce The Origin of the Family, a seminal work of Family Economics. The Communists are voracious readers who dismiss poorly conceived theory as part of their method. Marx probably read de Tocqueville but couldn't fit the anecdotes of a travelogue into his scientific method.

On the other hand--in support of Professor Possony's claim--neither de Toqueville nor Democracy in America are cited in Capital's "D" authors. Some of the included texts are: the "Daily Telegraph," Darwin, DeCartes and Diodorus of Sicily. "Toqueville, de" is also not wedged between Johann Heinrich von Thünen and Thomas Tooke. Among those international experts in the Communist bibliography, de Tocqueville is not overlooked as much as he is irrelevant, tangential or unnecessary.

Dr. Possony's other critique is originality. He derides the Manifesto as a "summation of all the radical ideas" of the Eighteenth century [xv]. This is true: Marx and Engels write much about Owen, Fourier and Saint Simon. Through dialectics the scientific socialists study the utopian socialists and essentially dismiss them as romantics who didn't evolve their theory with the mode of production.

Dr. Possony doesn't see the distinction and believes the Communists are copying, not learning. He does not engage with the Utopians. He states "communists have never yet presented useful and original reform ideas." [xxix]. The abolition of private property (like chattel slavery) might not be an original reform idea (this was never the claim). Abolition is certainly a useful tool for social and economic development proposed by many types of communists to counter lords, liberals and think-tank lecturers.

The Orwellian trick that Professor Possony pulls comes in the section "Socialism and Slave Labor." He relies on a de Tocqueville quote about the "confiscation" of liberty by socialists. He claims Engels promoted "transitory" slave labor to end private property. He also claims Marx advocated "permanent" slave labor after private property had been abolished [xxxi]. Doubleplus goodthink.

There is a semantic solution to this nonsense--if private property has been abolished then slavery is also a goner. A state has the monopoly on violence (with or without consent) and compels labor using a different lexicon than slavery. This includes: imprisonment, conscription, works program, or (in America) healthcare. Some of these modes are benign, trans-historical and even pro-social. Only people enslave other people. After the abolition of private property, chattel slavery (the ownership of one individual by another) is not possible. Therefore slavery is antithetical to the Communist Manifesto's stated goal of abolition; regardless of Professor Possony's confusion on de Tocqueville's behalf.

This is a discussion about democracy (to Marx, a critical step before communism is possible). Non-democratic states allow slaves. In non-democratic states, like the French monarchy, the leader and the state can be (apocryphally) confused. This is how the pyramids were built. But even here, the state doesn't own all slaves--it participates in the slave trade with other undemocratic states. This is one way Possony--most capitalists and liberals--confuse private property. There is a distinction between private property (owned by the state, corporations or individuals) and the personal property that communists understand as a trans-historical extension of usufruct.

We can presume no one chooses to be a slave. They are coerced. Therefore, in democracy, absent coercion, people don't become slaves without consent (by selling their labor or staying attached to the land) or social action (by violating norms and losing freedom). The cynic might point out modern American conditional Citizenship provides different democracies to different types of people based on things like age, phenotype, sex, service, religion or ethnicity. The Communists were not in favor of different types of citizenship for different types of people. The concept of internationalism is contrary to nationalists like de Tocoueville and Dr. Possony. The generations of nationalist Communists after Marx may have been inspired by the Dialectic but are viewed with suspicion by the Permanent Revolution sect of Trotsky and the Fourth International. The insufferable internal conversation about "true" communism usually incorporates a version of international vs. national politics.

Of the Manifesto itself there are only four pages underlined in my mom's worm eaten copy. They are consecutive [51-4] in "Proletarians and Communists". They are dismissive of critique, "[t]he charges against Communism made from a religious, a philosophical, and, generally, from an ideological standpoint, are not deserving of serious examination" [51]. This section is about old belief systems, based in previous class antagonisms, being inaccessible in a classless, proletarian society. The deconstruction of Christianity is one "radical rupture with traditional ideas" which might have been appealing to teenagers during the political upheaval of the long civil rights movement. On the other hand, the visible Christian (and Muslim) leadership confused this rupture and re-introduced morality from earlier epochs, reworked for the new struggle. Reading this didn't make my mom a Christian, Islamic National or Communist.

Marx' dismissal of "ideological" dissent might be the impulse that triggered Professor Possony. This is a fair emotional response when one's hero isn't included in an-other's pantheon. Possony should take solace in Marx' consultation with Darwin, Descartes and the Greeks. If he were acting in good faith as a dialectition, Possony's next step would be a good-faith comparison of de Toqueville and the Communists to see which conflicting concepts survived further scrutiny (and what was just conjecture from a field-trip). Faced with this prospect, Possony instead contracted with a deceptive publisher and began to snipe prospective students with his shallow, lengthy, pre-buttal.

So what is the point? Mostly this is a story about judging books by their covers. In another sense, it is about effective communication. How does the conservative movement entice teenagers? How does the left promote theory? What is the value of physical media? How do we encourage little worms to become butterflies without filling up on junk?